Ask the Expert: The Genetics of Inherited High Cholesterol

Healthline Magazine

July 2021

The Genetics of Inherited High Cholesterol

- Genetic mutations and cholesterol

- Homozygous FH

- Heterozygous FH

- Homozygous vs. heterozygous

- Is one form more dangerous?

- Passing FH to children

- Testing children for FH

- Detection and treatment

- Key tips to manage risk

How do genetic mutations affect cholesterol levels?

Genetic mutations can affect your cholesterol levels by changing the production or function of substances made by your body that transport or store cholesterol. These substances are called lipoproteins.

There are many ways that cholesterol production can be changed by genetic mutations, including:

- increased low-density lipoprotein (LDL)

- decreased high-density lipoprotein (HDL)

- increased triglycerides

- increased lipoprotein(a)

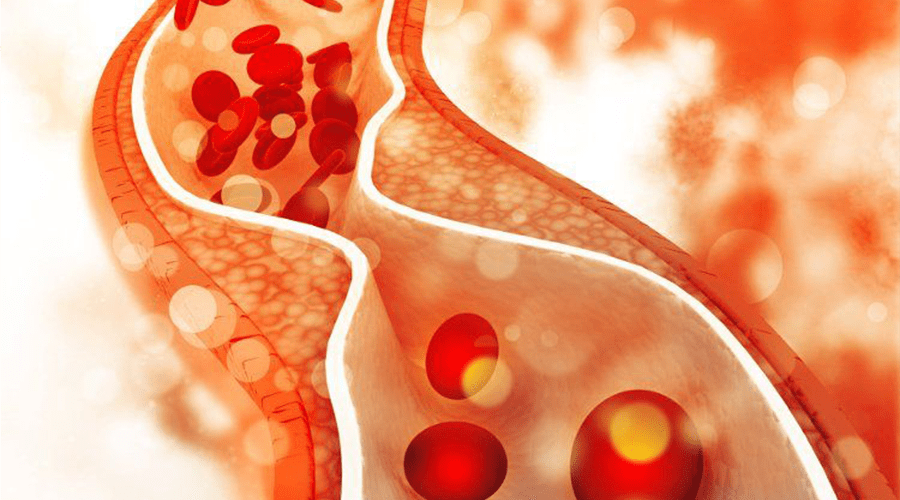

A very high increase in cholesterol level requires aggressive treatment. Most of the genetic disorders that affect cholesterol lead to very high levels of LDL and triglycerides, and people with these disorders may have cholesterol skin deposits and blocked arteries early in life.

Of all the lipoprotein disorders, the most research has been done on familial hypercholesterolemia (FH).

What is homozygous FH?

FH occurs when there is a mutation on one of your chromosomes for the LDL receptor. The LDL receptor plays an important role in the balance of your cholesterol levels. To have FH, you only need to have one mutated gene. This is called heterozygous FH.

Homozygous FH happens when both parents pass down the genetic mutation to the child.

Homozygous FH is an extremely rare disorder that causes very high LDL levels because of two mutated genes. People who are homozygous for FH have symptoms very early in life, sometimes even in childhood.

The extremely high LDL levels are difficult to treat, often requiring LDL apheresis, a procedure in which the blood has to be filtered to remove the LDL particles.

What is heterozygous FH?

Heterozygous FH occurs when only one parent has passed down the genetic mutation for the LDL receptor. Because of how this gene works, a person will still have FH with only one mutated gene.

With heterozygous FH, cholesterol levels are very high, but symptoms generally don’t appear in childhood. Over time, people may develop cholesterol deposits under their skin or on their Achilles tendon. Often, people with heterozygous FH have elevated LDL levels, but they aren’t diagnosed until their first coronary event, such as a heart attack.

How is homozygous FH different from heterozygous FH?

Homozygous and heterozygous FH differ in:

- how much LDL cholesterol levels become increased

- the severity and effects of the disease

- the treatments needed to control LDL levels

In general, people with homozygous FH have more severe disease and may show symptoms in childhood or their teen years. Their LDL levels are difficult to control with typical cholesterol medications.

People with heterozygous FH might not have symptoms until their high cholesterol levels start to form fatty plaque deposits in the body, which cause symptoms related to the heart. Generally, treatment will include oral medications, such as:

- statins

- bile acid sequestrants

- ezetimibe

- fibrates

- niacin

- PCSK9 inhibitors

Is one form more dangerous than the other?

Both forms of FH lead to early plaque deposits and heart events. However, people with homozygous FH tend to have signs earlier in life compared with people who have heterozygous FH.

If you have homozygous FH, your LDL levels are also more difficult to control, making it more dangerous in that regard.

How likely is it that FH will be passed on to children?

If one parent is heterozygous for FH and the other parent doesn’t carry the gene at all, their children will have a 50-percent chance of having FH.

If one parent is homozygous for FH and the other parent doesn’t carry the gene at all, their children will have a 100-percent chance of having FH because the one parent will always pass down a mutated gene.

If one parent is homozygous for FH and the other parent is heterozygous, all of their children will have FH.

If both parents are heterozygous for FH, there is a 75-percent chance that their children will have FH.

Should my children get tested?

Given that there’s a high chance that children can get FH from their parents, if you receive an FH diagnosis, it’s recommended that your children all get tested as well.

The earlier a child receives an FH diagnosis, the sooner the condition can be treated. Early treatment for FH may help your child avoid heart complications.

Why are detection and treatment important if I don’t have any symptoms?

Detection and treatment are very important if you have FH because high cholesterol levels at such an early age can lead to early coronary artery disease, stroke, and heart attack. High cholesterol levels in the blood can also lead to kidney disease.

People with heterozygous FH are often not symptomatic until their first heart attack when they are in their 30s. Once a plaque is deposited in the arteries, it’s very hard to remove the plaque.

Primary prevention before any major heart events occur is better than having to treat the disease complications after there has been damage to your organs.

What tips are most important to help manage heart disease risk with FH?

In order to reduce risk of heart disease, the most important lifestyle measures for people with FH are:

- Getting enough physical exercise. Exercise is the only natural way to raise HDL, the good cholesterol that can help protect against coronary artery disease.

- Preventing weight gain. Exercise also helps to manage weight and reduce the risk of diabetes and metabolic syndrome by decreasing fat.

- Eating the right foods. Cholesterol levels are affected by both genetics and dietary cholesterol, so people with FH need to adhere to a strict

low-cholesterol diet in order to help keep LDL levels as low as possible.

By maintaining this type of lifestyle, you may be able to delay heart events.

Dr. Joyce Oen-Hsiao is the director of clinical cardiology at Yale Medicine. She’s also an assistant professor of clinical cardiology at Yale School of Medicine. A graduate of Yale School of Medicine, she’s the director of cardiac rehabilitation at Yale New Haven Hospital (YNHH) Heart & Vascular Center and is also medical director of the cardiac rehabilitation program and co-director of the pulmonary hypertension program at the YNHH-St. Raphael Campus. Her interests include general cardiology, preventive cardiology, women’s heart disease, cardiac rehabilitation, and pulmonary hypertension.

Dr. Joyce Oen-Hsiao is the director of clinical cardiology at Yale Medicine. She’s also an assistant professor of clinical cardiology at Yale School of Medicine. A graduate of Yale School of Medicine, she’s the director of cardiac rehabilitation at Yale New Haven Hospital (YNHH) Heart & Vascular Center and is also medical director of the cardiac rehabilitation program and co-director of the pulmonary hypertension program at the YNHH-St. Raphael Campus. Her interests include general cardiology, preventive cardiology, women’s heart disease, cardiac rehabilitation, and pulmonary hypertension.