Long Work Hours Tied to Double the Risk for Recurrent MI

Batya Swift Yasgur MA, LSW

April 05, 2021

Patients who work upward of 55 hours per week after a myocardial infarction (MI) may increase their risk of having a recurrence, a new study suggests.

Over a 6-year period, investigators studied close to 1000 patients younger than 60 years who returned to work after a first MI. Those working 55 hours a week or more had a twofold increased risk for recurrent coronary heart disease (CHD) events, compared with those working 35 to 40 hours per week.

The risk further increased when the long working hours were combined with psychosocial stressors at work or with worse lifestyle risk factors, such as smoking, alcohol intake, and physical inactivity.

“The detrimental effect of working long hours after a heart attack is comparable to the burden of current smoking,” senior author Alain Milot,

MD, MSc, associate professor, Department of Medicine, Laval University, and clinical researcher, population health and optimal health practices, Axis Vascular Diseases Centre, Centre Hôpital Saint-François d’Assise CHU de Québec, Quebec City, Canada, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

“Long working hours should be assessed as part of early and subsequent routine clinical follow-up visits in order to improve the prognosis of patients who return to work after a heart attack,” he said.

The study was published in the April 6 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Overwork Common

Long working hours are common; according to the International Labour Office, roughly one-fifth of workers worldwide (>614 million people) work more than 48 hours per week, the authors write.

Previous research has shown a “deleterious effect” of long working hours on cardiovascular health, but no previous studies have examined the impact of long working hours on the risk for recurrent cardiovascular disease (CVD) events in patients who have had a first event, they note.

To investigate the question, the researchers prospectively studied 967 adults (aged 35 to 59 years) who returned to work after a first MI. The researchers collected baseline data about demographics, hospital readmissions, CHD risk factors, psychosocial factors (both inside and outside of work), and personality factors.

Follow-up telephone interviews were performed, on average, 6 weeks after the patient returned to work, and then at 2 and 6 years, with a mean follow-up time of 5.9 years.

Covariates included:

- Sociodemographic factors, including sex, age, marital status, education, and economic status.

- Clinical prognostic factors (previous comorbid conditions)

- CHD risk factors, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia

- Lifestyle-related factors, including alcohol consumption, smoking status, and physical activity.

- Work environment characteristics, such as job strain and low decision control

- Other factors, such as social support outside the work setting and personality factors.

Participants were divided into four groups, based on their total weekly work hours: • Part-time (21 – 34 hours per week)

- Full-time (35 – 40 hours per week)

- Low overtime (41 – 54 hours per week)

- Medium/high overtime (≥55 hours per week)

Prolonged Work Stress Exposure

During the study period, 21.2% of participants experienced a recurrent CHD event. Men were “over-represented” among those working at least 55 per week, compared with women (10.7% vs 1.9%), they note, as were younger workers who “perceived their economic situation as financially comfortable.”

Additional characteristics that were more frequent among individuals in the highest work category included CHD risk factors (hypertension, diabetes), lifestyle habits (smoking status, alcohol intake, and physical inactivity), and work environment situation (job strain, low support).

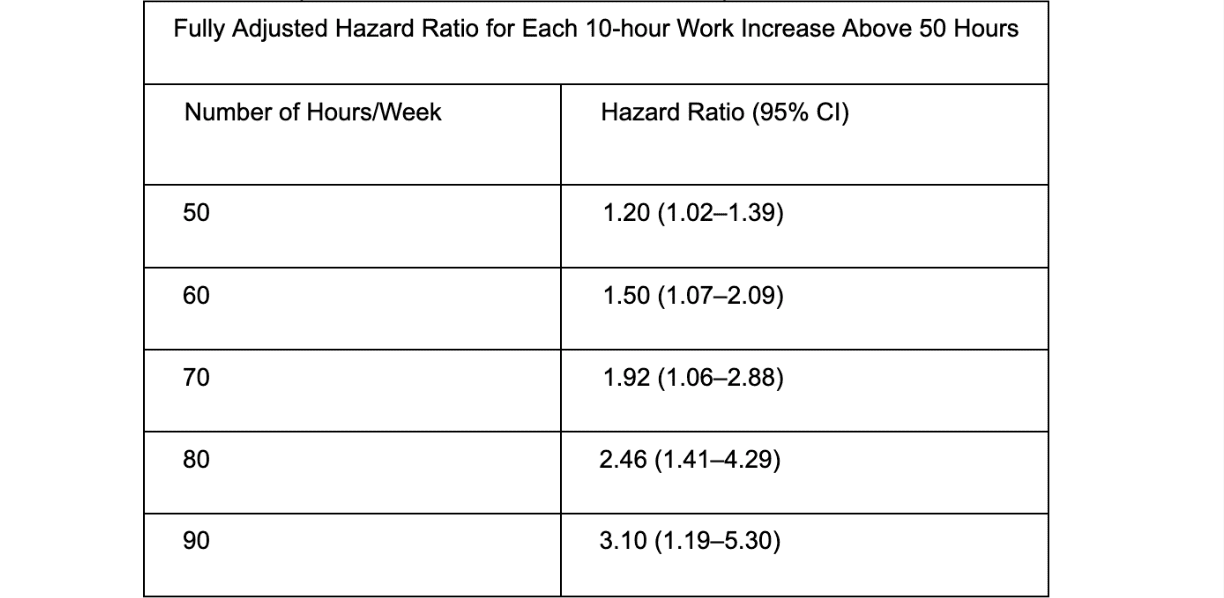

Compared with participants working 35 to 40 hours per week, those working at least 55 hours per week had a higher risk for recurrent CHD events, even after covariates were controlled for (hazard ratio, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.10 – 2.53).

The risk for recurrent CHD associated with a workweek of at least 55 hours “noticeably increased in magnitude after 4 years of follow-up,” especially when combined with job strain, the authors report.

Milot explained that long working hours could adversely affect cardiovascular health through several mechanisms, including the “deleterious effects of prolonged exposure to work stressors among those working longer hours.” Sleep deprivation is an additional factor since it has been shown to increase cardiovascular risk,” he said.

Previous research has shown that people working long hours have more unhealthy lifestyle habits, including a higher prevalence of smoking, physical inactivity and alcohol consumption that increase blood pressure, Milot suggested.

Quantity and Quality

Amir Lerman, MD, professor of medicine and director, Chest Pain and Coronary Physiology Clinic, Division of Ischemic Heart Disease and

Critical Care, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology that he found the study “thought provoking” and wonders: “Are we guiding patients correctly when we encourage them to go back to work immediately?”

Lerman, who was not involved with the study, added that not only the quantity but also the quality of work is relevant. “Is it merely the hours that the patient spends working, or does it reflect something more than hours, such as stress at work, relationships at work, type of work, and diminished time to unwind and release stress because of the longer working hours?”

He noted that more studies are required to understand the mechanism that might underlie the association, especially “if we need to modify our recommendation to patients following ACS [acute coronary syndromes] to return to work, and how much they can work.”

Milot agreed. “Future studies are needed to clarify the causal pathways linking long working hours and recurrent coronary events,” he said.

In an accompanying editorial, Jian Li, MD, PhD, professor, Department of Environmental Health Sciences, Fielding School of Public Health,

School of Nursing, University of California, Los Angeles, and Johannes Sie-rist, PhD, the Center for Health and Society, faculty of medicine,

Heinrich-Heine-University of Düsseldorf, Germany, conclude that this new study, “provides a new piece of research evidence that work related factors play an important role in CHD prognosis.

“Occupational health services are urgently needed to be incorporated into cardiac rehabilitation programs and secondary prevention of CHD,” they add.

This work was supported by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Québec and by the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec. The study and editorial authors and Lerman declare no relevant financial relationships.